28 Mar 2024

The championship boats that changed everything for New Zealand

World Champion coxswain from New Zealand, Andy Hay writes a tribute to the colour, characters and some of the centrepieces of the 1978 World Rowing Championships held at Lake Karapiro, New Zealand.

This is a story about boats. Boats that came by ship or plane, were freighted in on containers and crates, towed out of Lake Karapiro by car, truck or dusty Holden Ute and became the locomotives for generations of Kiwi rowers.

The reference to rail is important because this is a story for train-spotters who also love boats. And like any story for train-spotters, this one also partly takes place in a big shed.

Let’s start with the man who got the trains running in the first place.

Head of the organising committee Don Rowlands was a great dealmaker. He’d been chasing the dream of hosting the World Championships at Karapiro for a long time and got official discussions going in 1973 with the head of World Rowing (FISA back then).

After five years of lobbying, delegations to Europe, pitches to anyone with influence, New Zealand welcomed 27 other rowing nations and their fleets of A-list boats to the first world champs regatta ever held outside of the Northern Hemisphere.

It was a big deal however you measure it; whether it be the number of Kiwis who turned up to watch world class racing, or the number of special edition Leopard lager beer cans they sold in that toweling-hat beginning to summer in November 1978.

But one of the biggest deals was that as a condition of being awarded the championships, Rowlands and his tight-knit organising committee agreed to buy the guest nations’ boats at 80% of their factory price.

The boats would stay in New Zealand and be on-sold. Rowlands and co paid $390,801 for them. (Almost NZD$3m in today’s money).

Around 150 boats would be made available to the New Zealand rowing community. Most were pre-purchased through a points system that rewarded clubs and schools who’d bought a certain number of boats from local manufacturers in previous years.

When the dust settled New Zealand’s club, school and international rowing soared to a new level, our boatbuilding industry got a big shot in the arm and, to this day, there’s hardly a rower in New Zealand who hasn’t directly benefitted from those boats of nearly 50 years ago.

Big Red

There’s a moment that perfectly captures the spirit of the championships and New Zealand at the time. At Karapiro in ‘78 a group of local swimmers paddled out to offer a couple of cold beers to the East German (DDR) crew after they won the men’s eight on the final day of the regatta.

For New Zealand rowers there was a mystique about the DDR and in 1978 their crews were the benchmark for international rowing performance. They won eight of the 14 golds on offer in ‘78 and nothing signified that dominance more than their red BBG eight crossing the line first over West Germany and New Zealand.

The deal Rowlands had made meant that, for the first time, the DDR’s rarely seen plastic and timber composite boats would be left on foreign soil. Waikato Rowing Club bagged the men’s eight and it was to become the flagship of their rowing dominance for the next two decades.

New Zealand Olympic medallist Chris White was finishing his final year at Gisborne Boys’ High School in ‘78 when he made the long haul to join the massive crowds along the bank at Karapiro Domain.

“I was trying to find a decent seat underneath the grandstand…dodging beer cans. Me and my mates had come up for the day.”

Between ducking for cover he did get to see the red eight come down the course.

“Little did I know that a year or two later I’d be sitting in it, which is still surprising to me now,” says White.

It was the beginning of an incredible run of 11 successive national champion titles in the red eight for White.

“One of the things I liked about the red boat, it weighed a ton, we weighed it one time, it was 120kg plus. It was heavy, but it was big, so there was plenty of room for everyone to thrash around.”

It had been designed especially for Karapiro by the Godfather of boat design, Klaus Filter. He’d been messing about with boats since the 1940s and was East Germany’s principal designer through their golden period.

Filter made a special trip to New Zealand before the ‘78 champs to see for himself what conditions were like at Karapiro. He discovered what we all know. The side chop on the course can be brutal. So Filter went home and designed the East German boats for 1978 with extra high gunnels and cranked the seats and foot stretchers up off the floor as well.

It had an imposing presence whether you were in it or chasing it.

“I think it became a psychological thing,” says White. “Not only for us, but for the guys trying to race us and probably for no good reason other than it was an Eastie boat and it had won in 1978 and sometimes those things grow legs that they don’t deserve.”

The boat had other apparent attributes for those notoriously fast and aggressive-starting Waikato crews.

“Coach Harry [Mahon] told us that he thought the wake that came off it was significant. I don’t know whether that’s true or not. I guess if it’s got a big wake well that’s not a particularly efficient boat. But if we could get a length, we were thinking you start washing the other crew. Did it actually mean anything? Probably not. Was it fun to think about? Of course. Any advantage you could get, you would take.”

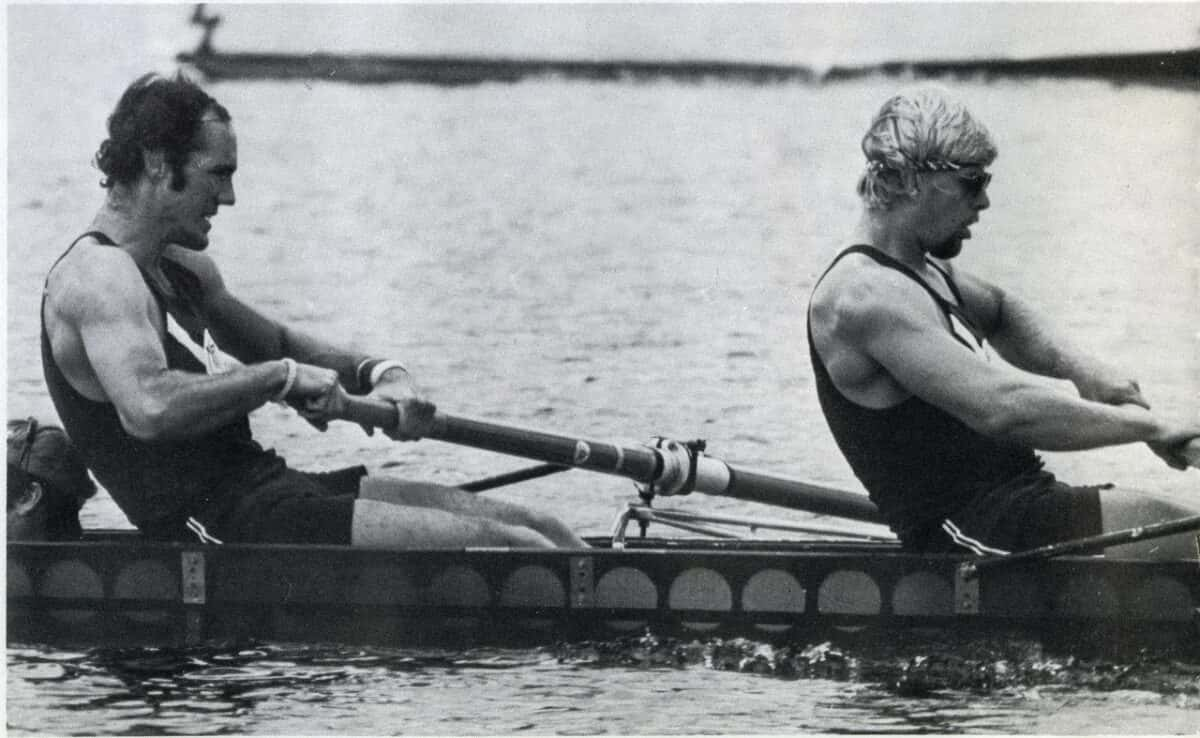

“It was built strong,” says Mark James, who stroked the Kiwi eight in ‘78 that year and sat in Big Red during his career at Waikato.

“You could see it had been built by a person who said, ‘Right, we need a big strong piece of wood here, we need a bit of doweling along the top, we need a good strong knee there, and we need glue between it’, and when they glued the joins, the glue squeezed out of the joint and it was still there. And then they slapped some varnish over it.”

The lustre remained for a long time. From 1981-1996 Waikato won 16 consecutive national titles in Big Red.

As James says: “The [DDR] boats were just robust, they were strong and reliable, and like Big Red, took a beating.”

But very rarely got beaten.

Big Red’s just a memory now, White hates the thought that it got cut up after he’d finished at Waikato. But a key thing survived.

Auckland Grammar School coach Colin Cordes used his own money to buy the other red DDR boat, the women’s boat which won silver and, despite the long-held belief of many, had the same hull as the men’s boat.

Transformational times

In ’78 Bob Rout was an apprentice boat builder to Alan Turner at Croker in Lake Karapiro’s closest town, Cambridge. He was also a novice rower. In the build-up to and during the champs – by day he helped with repairs, rigging and setting up all those boats. By night he and the other Cambridge rowers were running the public bar as a fundraiser for the club. In fact, there was absolutely no getting away from the rowers because the New Zealand squad was also staying at his parents’ motel in Cambridge.

It couldn’t have been a better introduction to the sport for the man who went on to build around 2000 boats under the Kiwi International Rowing Skiffs (KIRS) banner.

Rout’s first memory of the Empacher coxed four that was to become a central part of this story still leaves him shaking his head in disbelief.

“I remember seeing that arrive. It was shipped in for the US crew. When the box was opened at Karapiro it was in two pieces. It was almost as if the stevedore just took a bloody hacksaw to the boat, chucked it in the box and nailed it shut. So Malk Bergen [from Stampfli], myself and my boss Alan Turner glued it back together.”

The restored Doc Dardik, with its transparent honeycomb hull, helped the Americans to fourth in the A-final at Karapiro.

That piece of surgery was a surprise to Phil Stekl, the two seat of that American crew, when I tracked him down to his home in Seeboden, Austria.

“No!!!!, [I had] absolutely no idea. Absolutely no idea. The first time we saw it…was at the venue.”

The Dardik was definitely an upgrade on anything he’d rowed before.

“I mean, it wasn’t brand new, but it was stiffer than anything that I had remembered. Most of my early career we didn’t row in good boats. We weren’t rowing in Empachers, [that’s] for sure. And so to get a boat like this was pretty special.”

And while they were disappointed to just miss a bronze medal in their “fly and die” race for the line, 1978 will always be a defining year in Stekl’s life: his first national squad, his first world champs, his first time out of the States, and while waiting for a shuttle bus with his crew that November at Karapiro, he met an Austrian double sculler who would later become his wife.

The Doc Dardik ended up in the hands of the North Shore Rowing Club in Auckland.

Rout opened his own business in 1981 and his first mould came off the Doc Dardik, borrowed from North Shore in exchange for them getting his first hull.

The Shed

It’s time to take you inside that shed I mentioned. The shed that housed some of the locomotives.

You see not all those overseas boats sold immediately via Rowlands’ pre-purchase points system. Months later there was an auction. I tried to track down a catalogue. Luckily, one of Don Rowlands’ lieutenants, Cyril Hilliard, put it in his ‘Narrative of the 1978 World Rowing Championships’.

“Finally, all the boats purchased by the Organising Committee [excluding those already taken away] had to be de-rigged, labelled and transported to Auckland to be sold by auction … a total of 41 boats.”

One of the eights was a bow-coxed Empacher snapped up by Hawke’s Bay. Former rower Cedric Bayly reckons they bought it for about $7,000. It might just be the best $7k the club ever spent. Their lightweight eight won five successive national titles between 1978-82.

They won in a wooden Litecraft in ‘78 and ‘79 but the dynamic went off the dial when they hopped in the old West German boat for ‘80, ‘81 and ‘82.

“We just knew that when we stepped into that boat you had to do things right,” says Bayly. “You could feel everything. You could feel what was going well because of the speed of the boat and the run and the bubbles and that sort of thing. The wooden boats used to sort of be a bit dull, if you like, because the wood would absorb the feel of the boat at times.”

And like Big Red up at Waikato it gave its crew that sense of invincibility.

“It was like jumping into a race car. It just cut through any wash or waves or whatever. I think it displaced the water well around the bow and back along the canvas. It didn’t just cut at the bow so you actually got quite a smooth ride.”

I ask the big question.

“Hey Cedric, is the boat still there?”

I hold my breath for the answer.

“Yeah, it’s still a very slippery boat, you know. It always goes through the water well. I guess the important thing is that it’s almost 50 years old and it’s still helping younglings.”

I feel like jumping in the car and driving the five hours to Napier just to see it.

Boat Heist

Getting on the trail of one boat was a train-spotter’s dream. It was like searching for the Koh-i-Noor diamond. The East German men’s coxed four would become the jewel in the crown from the ‘78 sale. Gisborne Rowing Club paid $5,000 for it.

It attracted a big crowd when it arrived not long after the champs. The Gisborne Herald sent out a reporter for a story headlined “Rowers pleased with ‘golden’ shell” with coach Murray Whittaker saying, “it was the most sought after one at the championships.”

Whittaker knew they’d landed something special.

“This is probably the most technically advanced coxed four shell in the world. The East Germans spare no money when they go into research,” he told the Herald.

The caption beneath the picture of the boat on dumps said: “All we need now is the crew….”

Well, it got a crew alright, a unique bunch of “country boys” for a unique boat.

Peter Clark (str), Peter Scammell (3), Peter Godwin (2), Peter Johnson (bow), Barry Swarbrick (cox).

The Four Petes.

Peter Clark says they were serious podium contenders once they learned to row that red BBG.

“I have to admit we were all over the place for the first few rows with balance. Much lighter and more lively than the old wooden boats.”

The East Germans had two winning coxed fours at Karapiro in ‘78. The women winning their 1000m final in 3.48, nearly 4 seconds up on the United States.

Two beautiful red boats, two gold-medal winning boats. Gisborne getting the bigger men’s boat, Waikato somewhat disappointed at getting the smaller women’s boat.

Possibly hard to tell apart when it came to collection day.

Clark says he’s never received an apology for what happened next.

He remembers arriving with the Gisborne trailer to pick up their boat only to see a Waikato crew down at the dock preparing to row it back to their shed, the women’s four on the rack.

“We rushed down and said they had the wrong boat. They disputed it and it turned a bit nasty with name calling and threats… a member of Waikato said possession is 9/10 of the law so a Gisborne club member punched him… They were trying to bully us and we weren’t going to give up so a couple of us just picked the boat [up] and walked off with it and tied it onto our trailer while the arguing continued.

“It was a horrible thing that should never happen. It was not just a bit of mistaken identity it was theft…One of the worst bits of sportsmanship I ever have seen.”

‘Flopping’ boats

Viv Haar was in the New Zealand men’s pair in ‘78 but was also one of three local boatbuilders Rowlands needed agreement from to execute his plan to buy all the boats and on-sell them.

There were obvious downsides if you’re trying to keep a business going in a market flooded by a whole lot of state-of-the-art boats from overseas going for great prices.

But there was also an upside.

Haar calls it ‘flopping’ boats: getting a mould off a boat and reproducing the shape and fit-out, just like Bob Rout would go on to do hundreds and hundreds of times. And then there was the refurbishing all those Empachers, BBGs, Stampflis, Kaschpers and Donaraticos would eventually need.

Haar flopped plenty of those shapes. As well as the Doc Dardik, he got Auckland Grammar’s DDR women’s eight, and Hawke’s Bay’s West German Empacher. He got the East German pair rowed by Bernd and Jorg Landvoight, the famous twins, who between 1974 and 1980 lost only one of their 180 races together.

The Doc Dardik mould was the shape for all Rout’s coxed fours until 1991. His pair and double shapes continued through to 1996. His East German eight went all the way to 1998, and his Empacher shape got all the way through to 96.

The final search

Plenty of people knew strands of the story about the attempted heist but only one person knew what eventually happened to the men’s boat. Peter Clark thought it had ended up at the Wairau Rowing Club.

I got hold of Mark James, the man who stroked the Kiwi eight against Big Red all those years ago. He was getting off the water from a training row.

Yep, Wairau bought it off Gisborne. It stayed on the rack unused. James hoped Marlborough Boys College might row it when they came onboard. But that never happened.

Space was tight these days, Andy.

I was holding my breath, hoping.

We burned it last month mate.

I nearly cried.

A Personal Footnote

One of the first boats Bob Rout built when he was at Croker was a new senior eight for Westlake High School in 1978. It was called the Eric Craies in honour of the man whose influence is still huge in New Zealand rowing.

I steered the Craies for three years before joining North Shore and jumping into the Doc Dardik. I would describe it as “industrial” with all that aluminium in it. But definitely a fast boat. At Nationals in 1982, I was also given dispensation to cox Waikato’s Chris White and Andrew Stevenson in their green DDR 2+. Incredible boat and I learned the value of knowing when not to talk. By August of that year, I was sitting in a new generation Empacher eight at Lucerne.

The other day I got in the car early on a beautiful Auckland morning and in a slightly cringy way put Van Halen’s ‘Jump’ full bore on Spotify and headed to rowing training with a big smile on my face.

It might just be the best song ever. It reminds me of heading for Lake Casitas in the van with the radio blasting in the North American summer of 1984 LA Olympics with my crew and my coach.

And despite the disappointment of being just a couple of weeks late from saving that East German four, I dug up another treasure.

I’m now the proud guardian of an abandoned Stampfli eight from that life-changing ’78 regatta.

I love this sport.

Andy Hay

Article shared with permission from Rowing NZ’s content hub www.rowinghub.co.nz. Article written by Andy Hay, a freelance producer, writer and rowing coach. He was cox of the world champion New Zealand eight of 1982 and ’83. He is NZ Olympian #446.